The Art of Biltmore’s Open-Air Museum

Written By Joanne O'Sullivan

Posted 08/10/15

Updated 07/22/22

In Our Gardens

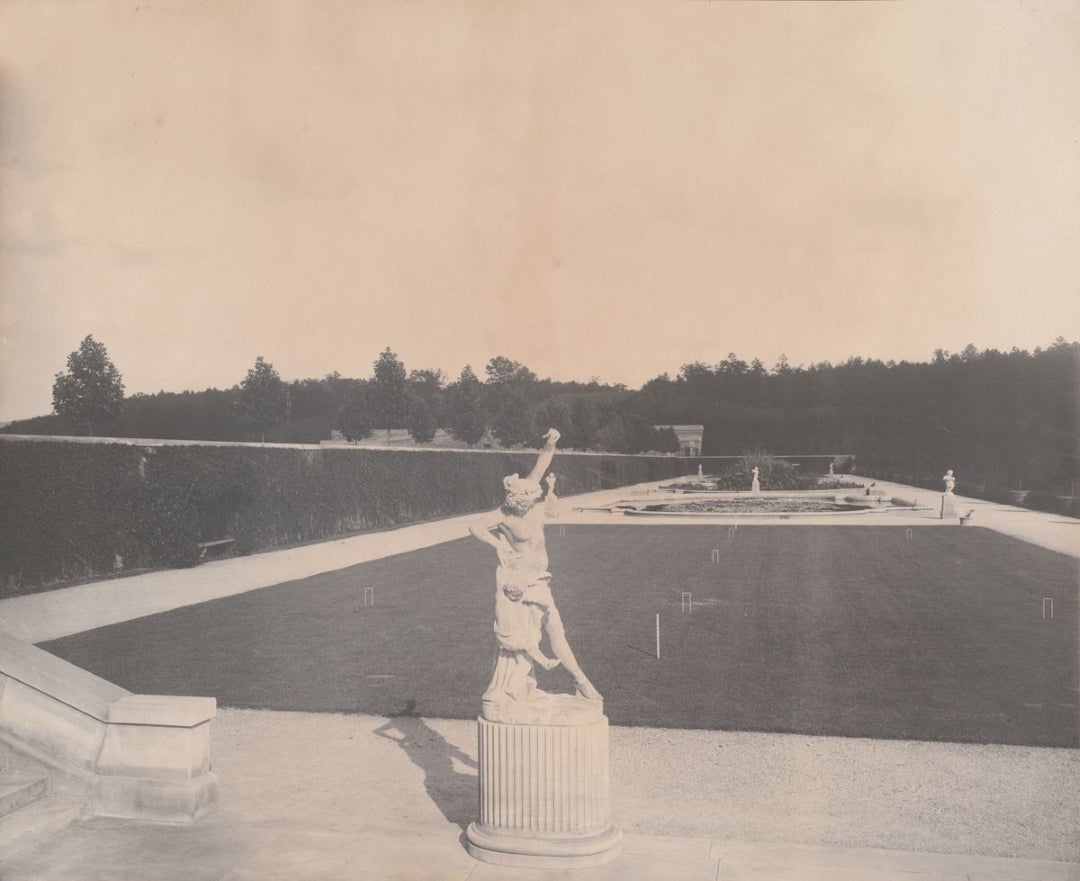

Frederick Law Olmsted selected the major plantings at Biltmore with the utmost attention. Each had a specific purpose: to provide a certain color, texture or function, such as shade or height. But the manmade features of the gardens−statuary and planters−are more like the icing on the cake, hitting graceful notes throughout the landscape. So, what do we know about the artwork in Biltmore’s open air museum?

“To our knowledge, Olmsted did not specify any statuary at Biltmore,” says Bill Alexander, Biltmore’s Landscape and Forest Historian. Research shows most of the statues were purchased in the late 1800s in France and Italy by George Vanderbilt and Richard Morris Hunt, Biltmore’s architect. It’s likely that Olmsted did play a role in the placement of the statues because the three men worked so closely on every aspect of the design of Biltmore House and Gardens.

Classic Influences

Walking through the gardens, you’ll notice a number of statues featuring characters from Greek myth. The four terra cotta figures on the South Terrace—Faun, Adonis, Venus, and Hamadryad—are modeled after originals created by Antoine Coysevox, a prolific sculptor from the 17th century. If you look closely at the figure at the far right end of the Terrace, you’ll see Coysevox’s maker’s mark.

In the Italian Garden, you’ll find several variations of late-19th-century putti—winged figures that were popular in both statuary and painting during the Italian Renaissance. The small terra cotta angel located at the end of the Italian Garden is based on a work of art that’s housed in the Louvre. Although there’s a fountain bowl in front of this putto, Kara Warren, Preventive Conservation Specialist, says there is no record that water was ever used in the fountain.

Aging Naturally

Whether made from bronze, marble, limestone, granite, or terra cotta, each outdoor statue has to weather the elements. Storms and environmental pollutants have taken their toll of them over the last century. According to Kara, some repairs and restorations date back to 1934.

“Reading the descriptions of repair work from our archival records is like having a mini history lesson. Each repair documents the care the statue received over the year. Today, we occasionally need to repair the repairs, replacing corroded iron elements with stainless steel or replacing mortar that has crumbled over time,” she continues.

Near the stairway leading from the house to the Italian Garden, you’ll notice the Italian white marble statue that’s known as “The Dancing Lesson.” The original, made of terra cotta, was replaced by this copy in the 1970s after it was damaged in a storm.

Perhaps Biltmore’s most famous statue, Diana, goddess of the hunt, located on the hill overlooking the house, met a similar fate. The original terra cotta work, based on a marble housed in the Louvre, was replaced with today’s marble version carved by H. Whinery Oppice in the 1970s.

In Harmony with Nature

As you walk through the gardens, statuary sometimes plays a supporting role to the ever-changing natural beauty that takes center stage. But each garden element is an important part of this living landscape that has been recognized as a National Historic Landmark.