Rosita, by Spanish painter Ignacio Zuloaga (1870–1945), is one of the most eye-catching works in George Vanderbilt’s collection and represents his interest in Spanish art, which gained popularity in the last years of the 19th century.

Lounging on a divan draped with a mantón de manila (a flamenco dancer’s accessory), Rosita is wrapped in a white fringed shawl with a red floral flamenco skirt billowing out. She leans on her elbow and smiles, a huge red flower in her dark hair. Rosita is confident: a model at ease with being an object of beauty. So, how did this captivating woman come to stay permanently at Biltmore?

A celebrated artist

In 1913, Zuloaga, known as “The Great Basque,” was living in Paris where his reputation had grown since his first exhibition in 1890. He came from a family of artists and his great-grandfather was a contemporary of Goya, who Zuloaga cited as one of his major influences.

A rising star in the art world by the turn of the century, Zuloaga was known for his portraits, especially those of women with a great deal of personality. He also had a reputation for hosting memorable Parisian parties attended by artistic luminaries of the day, such as the famed conductor and cellist Pablo Casals.

“To draw another connection to Biltmore’s collection, we know that he was respected by John Singer Sargent, who actually wrote the introduction to a 1914 catalog of Zuloaga’s work on display in Boston,” says Meghan Forest, Biltmore’s Associate Curator.

Modern art, circa 1914

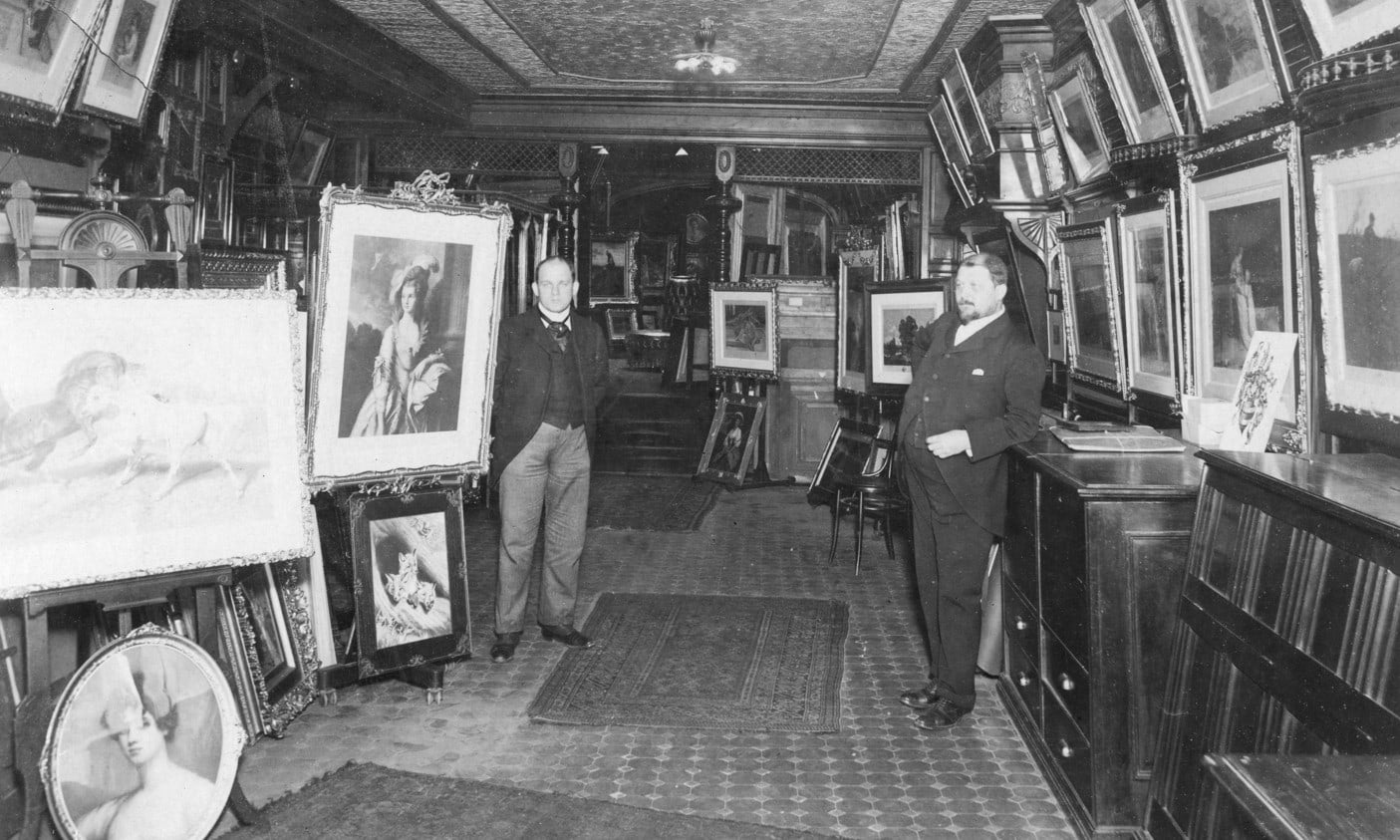

In January 1914, an American exhibition of Zuloaga’s paintings was held at the prestigious Kraushaar Galleries at 260 Fifth Avenue in New York. The show was reviewed in the February issue of Art and Decoration, a leading art journal of the time:

“Mr C W Kraushaar, following up on his success of last season, showed for two weeks eight pictures by Ignacio Zuloaga, the greatest realist of the very realistic Spanish school.”

The article goes on to say that “his Rosita, in the pattern of her shawl and of the couch on which she reclines, is masterly in painting.”

According to Meghan, recent research on their correspondence indicates that George Vanderbilt did in fact attend the exhibition. He wrote to Kraushaar in January 1914 offering to purchase the painting and requesting the frame in which it is displayed today inside Biltmore House.

Rosita finds a home at Biltmore

After George Vanderbilt’s death, Edith Vanderbilt paid for the painting and requested that it be sent to a museum rather than to Biltmore. In 1915, Rosita entered the collection of the National Museum (now the Smithsonian American Art Museum) on loan. There she stayed until 1924, when Cornelia Vanderbilt Cecil and her husband, the Honorable John Francis Amherst Cecil, visited to view the painting and requested its return to Biltmore. The painting arrived in December 1924, with Rosita taking her place as one of Biltmore’s most intriguing permanent residents.

While Rosita was not at Biltmore during George Vanderbilt’s lifetime, our records indicate that her first placement was the Second Floor Living Hall—a decision made by Cornelia and John Cecil. She was later displayed in the Billiard Room in the 1970s before taking up residence in the hallway outside of the Louis XV Suite in more recent years.

Conserving Rosita

In 2023, Biltmore’s in-house conservator, Nidia Navarro, completed the conservation treatment of Rosita’s ornate frame while the painting itself was sent to Ruth Barach Cox for conservation. The painting conservator worked to remove old, discolored varnish and overpainting that was added during past conservation treatments and restore the vibrant colors and brush strokes to their original splendor. Early photos of the painting and Cox’s inspection revealed that the original work featured body hair in the sitter’s armpit, a common practice around the world in the early 20th century. Cox’s treatment returned the painting to its original appearance.

Be sure to look for the recently conserved Rosita painting on display in the hallway outside of the Louis XV Suite on your next visit to Biltmore House.

Both of Edith’s parents both passed away in 1883, but the children’s elderly maternal grandparents stepped in to raise the five siblings who ranged in age from six to nineteen. The young Dressers moved to their grandparents’ home in Newport, and a governess named Mademoiselle Marie Rambaud was added for the girls. Pauline’s memoirs mention how Mademoiselle Rambaud had the Dresser girls adhere to the following regime:

Both of Edith’s parents both passed away in 1883, but the children’s elderly maternal grandparents stepped in to raise the five siblings who ranged in age from six to nineteen. The young Dressers moved to their grandparents’ home in Newport, and a governess named Mademoiselle Marie Rambaud was added for the girls. Pauline’s memoirs mention how Mademoiselle Rambaud had the Dresser girls adhere to the following regime: Following the death of their grandmother in 1892, Edith and her sisters spent some time traveling, returning to Newport for a few months before taking an apartment in Paris for the next several years.

Following the death of their grandmother in 1892, Edith and her sisters spent some time traveling, returning to Newport for a few months before taking an apartment in Paris for the next several years.

How our tradition began

How our tradition began The celebration continues

The celebration continues “A Vanderbilt Christmas”

“A Vanderbilt Christmas”

Adorning the top of such a grand tree, there must be an equally grand tree-topper. Each year, Biltmore’s floral team envisions and then creates a tree-topper in keeping with the Christmas theme, the size of the tree, and the immense scale of the Banquet Hall.

Adorning the top of such a grand tree, there must be an equally grand tree-topper. Each year, Biltmore’s floral team envisions and then creates a tree-topper in keeping with the Christmas theme, the size of the tree, and the immense scale of the Banquet Hall. Two years later, Simone Bush, Biltmore Floral Designer and Wedding Consultant, drew on the idea of families coming together at the holidays, and the wonderful, whimsical ways in which their joy might be expressed, to create a charming, light-hearted tree-topper beribboned like a jester’s staff, delighting everyone who saw it atop the towering tree.

Two years later, Simone Bush, Biltmore Floral Designer and Wedding Consultant, drew on the idea of families coming together at the holidays, and the wonderful, whimsical ways in which their joy might be expressed, to create a charming, light-hearted tree-topper beribboned like a jester’s staff, delighting everyone who saw it atop the towering tree.

According to winemaker Bernard Delille, The Hunt has been aged for about 18 months in French and American oak barrels. “The intensely dark, black cherry color shows its rich layers, while its nose expresses black cherry, blackberry, and raspberry, with notes of vanilla, oak, and chocolate,” said Bernard.

According to winemaker Bernard Delille, The Hunt has been aged for about 18 months in French and American oak barrels. “The intensely dark, black cherry color shows its rich layers, while its nose expresses black cherry, blackberry, and raspberry, with notes of vanilla, oak, and chocolate,” said Bernard. “Francotte’s sporting firearms were considered to be among the highest quality,” said Leslie Klingner, Biltmore’s Curator of Interpretation, “and would have been a first-rate choice for the Vanderbilts and their guests when shooting rabbits and quail.”

“Francotte’s sporting firearms were considered to be among the highest quality,” said Leslie Klingner, Biltmore’s Curator of Interpretation, “and would have been a first-rate choice for the Vanderbilts and their guests when shooting rabbits and quail.”