To discover George Vanderbilt’s railroad ties, you have only to look at his family history.

Few names have been more closely associated with the rise of the American railroad industry than the Vanderbilts.

Theirs is a remarkable legacy, and one that would ultimately contribute to the development of Biltmore, George Vanderbilt’s magnificent private estate.

Portrait of Cornelius “Commodore” Vanderbilt in the Breakfast Room of Biltmore House

Portrait of Cornelius “Commodore” Vanderbilt in the Breakfast Room of Biltmore House

Railroad legacy

The Vanderbilt family’s success began with George Vanderbilt’s grandfather Cornelius “Commodore” Vanderbilt—an entrepreneur from modest beginnings who spent his life building an empire based on shipping and railroad concerns.

His son William Henry Vanderbilt inherited the business after the Commodore’s death in 1877, doubling the family fortune before he passed away nine years later.

Cornelius Vanderbilt II and William Kissam Vanderbilt, William Henry’s two oldest sons, followed in their father’s footsteps to take on management of the family’s holdings, leaving George Vanderbilt—the youngest of William Henry and Maria Louisa Kissam Vanderbilt’s eight children—free to explore his interests in art, literature, and travel.

George Vanderbilt’s vision

Formal photographic portrait of young George Vanderbilt

Formal photographic portrait of young George Vanderbilt

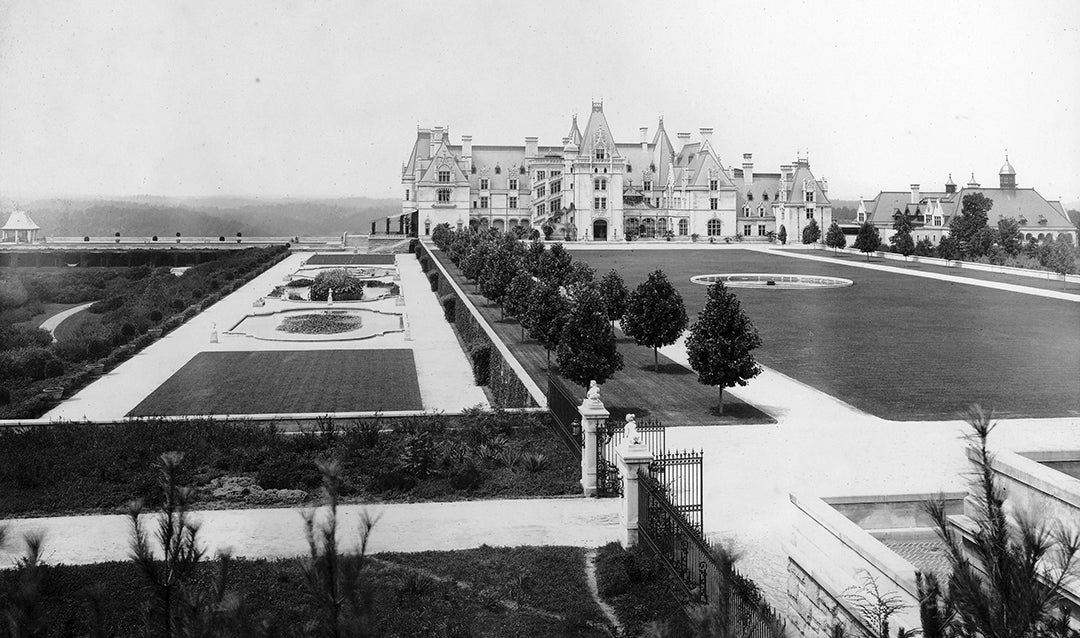

By the time George Vanderbilt was in his twenties, he had begun planning the creation of a country estate similar to those he’d visited in Europe. After settling on Asheville, North Carolina, as the setting for his new home, he purchased considerable acreage in the area, breaking ground in 1889 for what would become Biltmore.

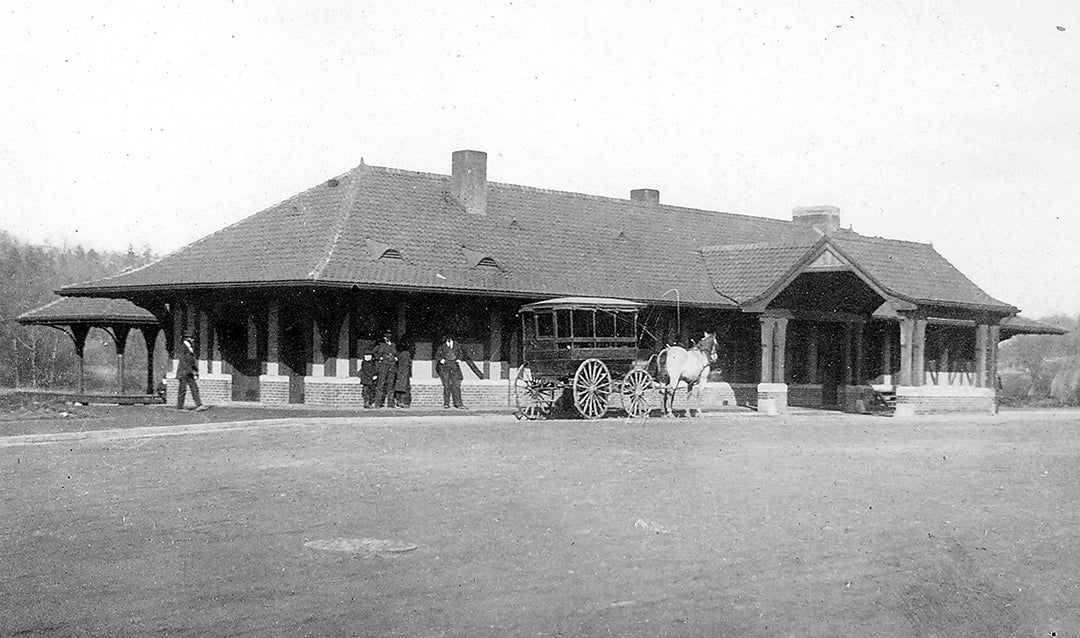

Vanderbilt party near Biltmore Station; March 1891. Seated (L-R) are Margaret Bromley, Maria Louisa Vanderbilt, Marguerite Shepard, and two unidentified women; unidentified person seated behind Mrs. Vanderbilt. Standing (L-R) are Margaret Shepard, possibly Frederick Vanderbilt, and George Vanderbilt.

Vanderbilt party near Biltmore Station; March 1891. Seated (L-R) are Margaret Bromley, Maria Louisa Vanderbilt, Marguerite Shepard, and two unidentified women; unidentified person seated behind Mrs. Vanderbilt. Standing (L-R) are Margaret Shepard, possibly Frederick Vanderbilt, and George Vanderbilt.

While maintaining a permanent address at his family’s Fifth Avenue home, George made frequent trips to Asheville to oversee the project during the six years that Biltmore was under construction.

Swannanoa

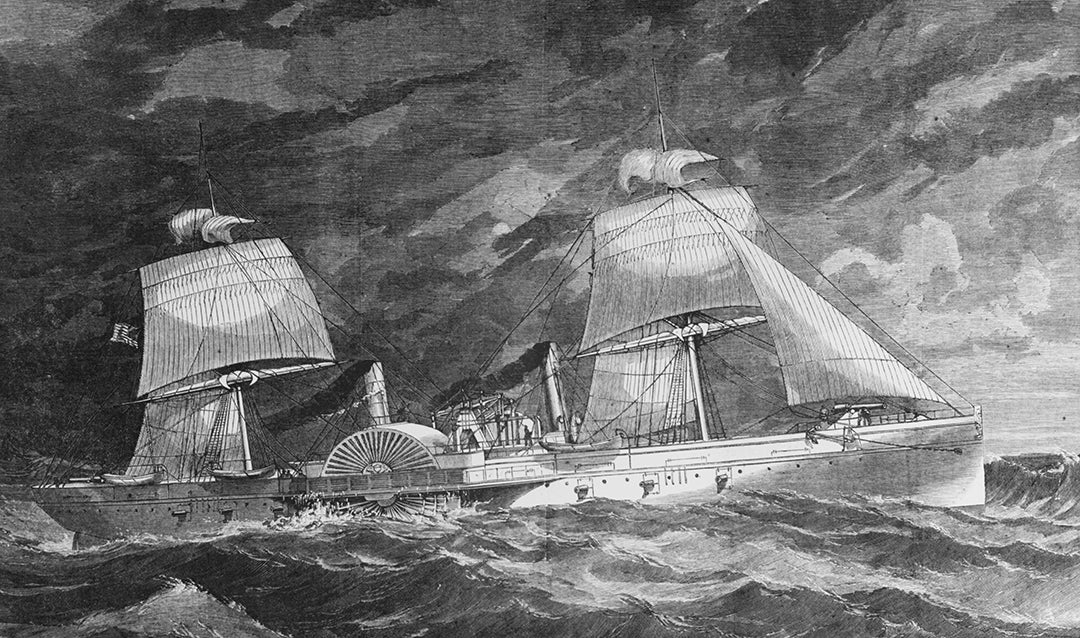

In 1891, George Vanderbilt furthered his railroad ties by commissioning a private railcar from the Wagner Palace Car Company of Buffalo, NY. Showing affinity for his new home, George named his railcar Swannanoa after one of the two rivers that flowed through the property.

“Private railcars like Swannanoa were the height of luxury in the golden age of railroad travel, functioning as a home away from home for wealthy travelers” said Darren Poupore, Chief Curator for Biltmore.

For the railcar’s inauguration, Maria Louisa Vanderbilt gave her son an engraved tea service that read “GWV from MLV, November 14, 1891, Swannanoa.”

Teapot from Swannanoa’s tea service

Teapot from Swannanoa’s tea service

Luxury travel

Swannanoa’s mahogany-paneled parlor was furnished with plush chairs and sofas; staterooms accommodated up to 12 people with comfortable beds and other furnishings.

George often sent Swannanoa to Washington and New York to transport family and friends back to Biltmore. While on board, a cook provided elaborate meals from a well-appointed kitchen and a porter tended to every passenger’s needs.

In addition to those comforts, guests could admire scenic views through plate-glass windows in an observation room in the rear of the car. And just like Biltmore House, Swannanoa’s interiors reflected George’s personality and interests, complete with countless books and etchings from his collections.

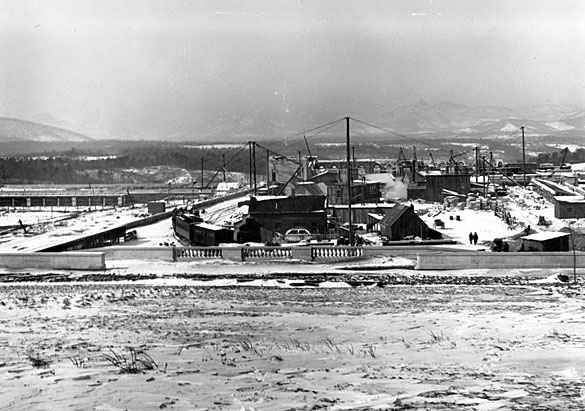

View of Biltmore’s Rampe Douce and Vista with construction sheds and train in foreground, c. 1892

View of Biltmore’s Rampe Douce and Vista with construction sheds and train in foreground, c. 1892

Estate construction

As work on Biltmore House continued, a contract between estate architect Richard Morris Hunt and the project’s general contractor stipulated that the massive quantities of Indiana limestone required for construction be shipped by rail directly to the house site.

Working with a civil engineer and consulting with the superintendent of the Richmond & Danville Railroad, landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted laid out a route for a standard gauge rail line connecting the depot in Biltmore Village to the building site.

The area’s uneven terrain—alternating between deep hollows and ridges—presented an added challenge for the rail line. In order to create a gradual incline from the depot to the building site, five trestles with a total length of 1,052 feet were constructed to carry the train across the gullies.

Steam locomotive in front of the Rampe Douce during construction; June 9, 1892

Steam locomotive in front of the Rampe Douce during construction; June 9, 1892

More railroad ties

George Vanderbilt purchased three steam locomotives for use on the estate. The two standard-gauge locomotives operated on the main railroad line to the Esplanade.

The first, Engine No. 75 (later renamed Cherokee) was purchased in 1890, but had to be modified because it lacked the coal and water capacity to make one trip to the Esplanade.

Another standard-gauge Baldwin locomotive, aptly named Biltmore, became the workhorse of the three engines.

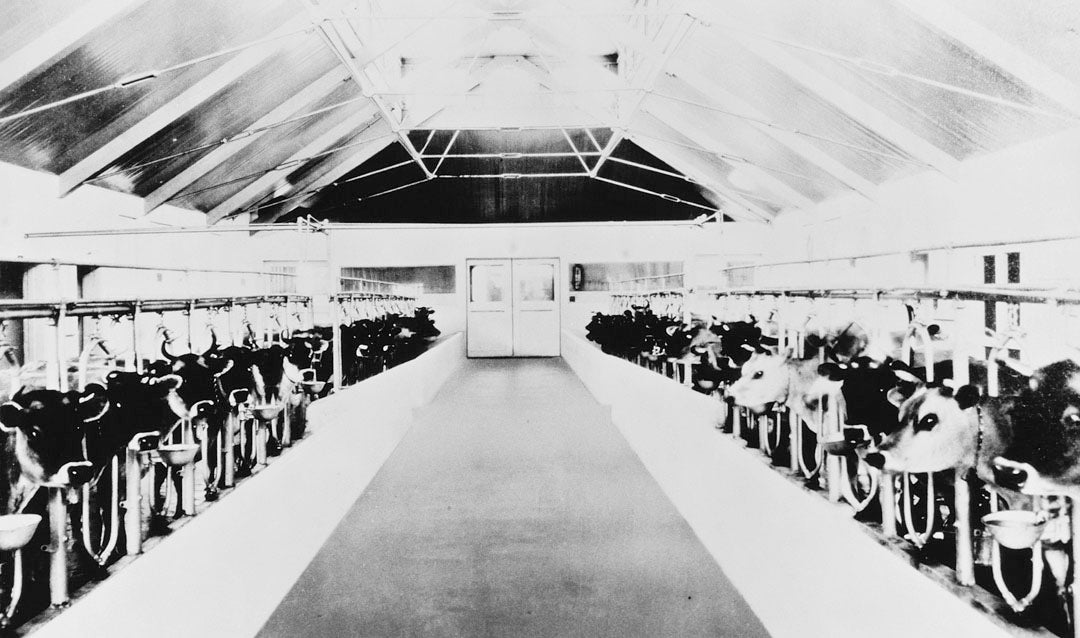

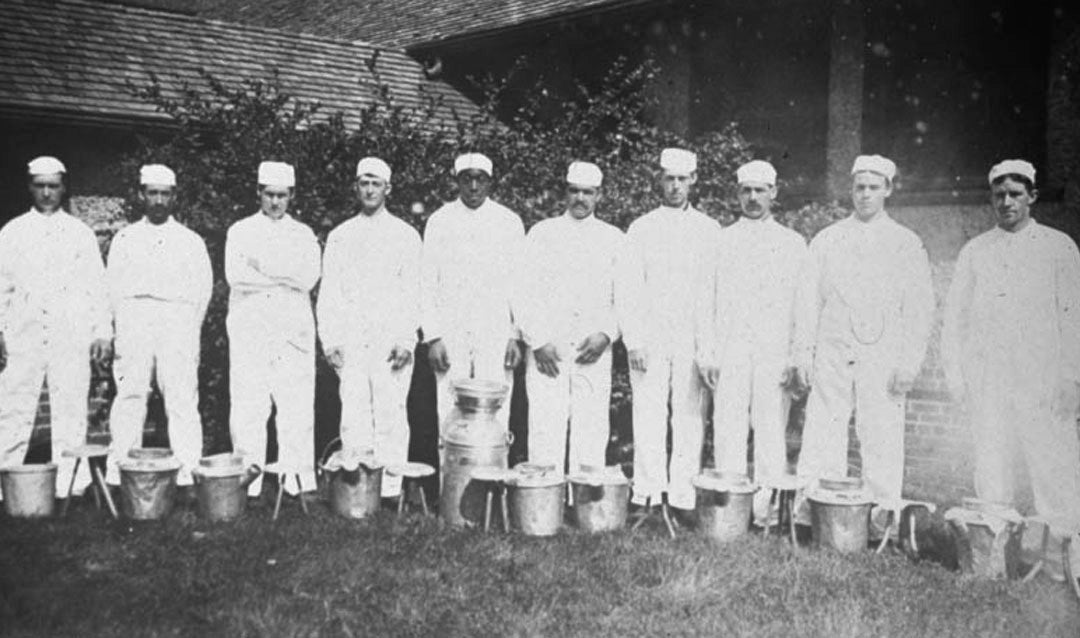

Workers with a Baldwin steam engine on the Esplanade, 1892

Workers with a Baldwin steam engine on the Esplanade, 1892

The third locomotive, named Ronda, was a smaller engine used solely on the narrow-gauge line that ran between the Biltmore Brick and Tile Works and the clay pits on the estate.

After construction ended, the railway was disbanded and the steam engines were sold, but today’s guests can still see remnants of the railroad’s path in a few places around the estate.

Discover Biltmore Gardens Railway

Biltmore Gardens Railway display

Biltmore Gardens Railway display

From July 1–September 7, 2020, enjoy Biltmore’s historic landscape from a new perspective: accented with model trains and replicas of iconic American train stations during Biltmore Gardens Railway.

On display in Antler Hill Village, this charming exhibition showcases handmade buildings constructed of natural materials like leaves, bark, and twigs and large-scale botanical railways.

Plan now to enjoy this one-of-a-kind, fun-for-all-ages experience that honors George Vanderbilt’s railroad ties.

Featured image: Unidentified passengers gathered on the back of what is thought to be Swannanoa, George Vanderbilt’s private railway car

Portrait of Cornelius “Commodore” Vanderbilt in the Breakfast Room of Biltmore House

Portrait of Cornelius “Commodore” Vanderbilt in the Breakfast Room of Biltmore House Formal photographic portrait of young George Vanderbilt

Formal photographic portrait of young George Vanderbilt  Vanderbilt party near Biltmore Station; March 1891. Seated (L-R) are Margaret Bromley, Maria Louisa Vanderbilt, Marguerite Shepard, and two unidentified women; unidentified person seated behind Mrs. Vanderbilt. Standing (L-R) are Margaret Shepard, possibly Frederick Vanderbilt, and George Vanderbilt.

Vanderbilt party near Biltmore Station; March 1891. Seated (L-R) are Margaret Bromley, Maria Louisa Vanderbilt, Marguerite Shepard, and two unidentified women; unidentified person seated behind Mrs. Vanderbilt. Standing (L-R) are Margaret Shepard, possibly Frederick Vanderbilt, and George Vanderbilt. Teapot from Swannanoa’s tea service

Teapot from Swannanoa’s tea service View of Biltmore’s Rampe Douce and Vista with construction sheds and train in foreground, c. 1892

View of Biltmore’s Rampe Douce and Vista with construction sheds and train in foreground, c. 1892 Steam locomotive in front of the Rampe Douce during construction; June 9, 1892

Steam locomotive in front of the Rampe Douce during construction; June 9, 1892 Workers with a Baldwin steam engine on the Esplanade, 1892

Workers with a Baldwin steam engine on the Esplanade, 1892 Biltmore Gardens Railway display

Biltmore Gardens Railway display

Sip a glass full of spring with us

Sip a glass full of spring with us